African Canadian quilting emerged in the decades preceding Confederation. Enslaved Black women were used for spinning, weaving, sewing and quilting on American plantations. When the first generation of fugitive slave women arrived in Canada – the “land of freedom” – in the 1840s, they brought with them the skills and talents they too would pass down to their children.

The village of North Buxton, near Chatham, ON, is situated in what was once known as the Elgin Settlement, or more commonly, the Buxton Settlement. Its founding owes much to slavery having been abolished in Canada after 1834, and Chatham serving as a northern terminus for the Underground Railroad before the American Civil War.

The village began in 1849 when Reverend William King and an association with abolitionist principles known as the Elgin Association secured 9000 acres that were made available to fugitive American slaves or to any free Blacks that were looking for opportunities for a better life. This seed community continued to grow and prosper in the years leading up to emancipation in the United States (1865). At its peak, nearly 2000 people lived in and around what was termed the most successful of all the planned settlements for fugitive slaves.

The Busy Bee is a signature quilt made in 1924 by the Busy Bees Women’s Society

The Busy Bee is a signature quilt made in 1924 by the Busy Bees Women’s Society

with their names in the centre.

Today, the majority of the population of the village consists of descendants of some of its original families. Throughout, there has been a strong sense of community instilled in everyone.

When Reverend King arrived in 1849, he brought with him 15 former slaves, seven of them women. These women, who left behind a life of slavery, would now embark on a new life in freedom. They would try to grasp and understand its meaning, learn how to be mothers and wives, and know the joys of family and community, all while realizing the sorrows they left behind.

(L) Hand pieced and quilted by Julia Ann Doo, this signature quilt was completed by her great granddaughter, Julia Shreve. Made of cotton and comprised of pieced squares and triangles, it features blocks with a variety of centres which include the words Buxton 1884, Jula Doo, Just As You CE Us and I Hope.

(L) Hand pieced and quilted by Julia Ann Doo, this signature quilt was completed by her great granddaughter, Julia Shreve. Made of cotton and comprised of pieced squares and triangles, it features blocks with a variety of centres which include the words Buxton 1884, Jula Doo, Just As You CE Us and I Hope.

(R) This Nine Patch quilt was pieced and quilted by an enslaved Black woman in 1848. Finely stitched cotton quilts were prized possessions made more for display than for warmth. They infused light and beauty into the bedroom and were passed along from one generation to the next.

They worked beside the men, not only clearing the land and building homes for their families, but also providing comfort and encouragement that would strengthen and unify the community. With them they brought their artistic abilities, readily visible in the quilts made from scraps and used clothing that kept their families warm. Also within the quilts can be seen some of the unique patterns that were representative of their culture. Observers can almost envision the women of Buxton creating these marvelous colourful coverings and deftly employing such fine detailed stitches that seem almost transparent to the naked eye.

From the 19th century on into the next, the women in the settlement put their abilities to work by organizing clubs for the betterment of the community. Fully realizing the importance of education, religion and family, these dedicated women ran the clubs to nurture, counsel and give guidance to their children.

As one example, the Sunshine Club from the local British Methodist Episcopal Church (now the North Buxton Community Church) established quilting bees. A quilting frame would be set up and remain in a home until the quilt was finished. Work on a quilt was a gathering time for women to get together to socialize; it usually lasted four hours. This was a time to share news, exchange recipes and provide child-rearing tips – generally offering support for one another.

The Log Cabin quilt design appeared in Canada in the late 1860s. Traditionally, at the centre of each block was a red square, believed to represent the hearth, with alternate light and dark strips for the sunny and shady sides of the house. Another meaning to the strips is happiness (the light side) and sorrow (the dark side), of which life is filled. This one was made by the women in the community for Reverend King. In addition to wool, which was readily available, a variety of materials, from clothing scraps and blankets, came to Canada after the American Civil War. Vibrant pinks and reds in velvets, satins and silks are scattered throughout.

As the quilters met regularly, the stories about the harsh times their ancestors suffered began to flow; they shared how blessed they felt in their new lives. Before too long, some of these stories were delicately stitched into beautiful masterpieces. The women of North Buxton clearly recognized there was a necessity to preserve their memory of community and personal achievements for the next generation.

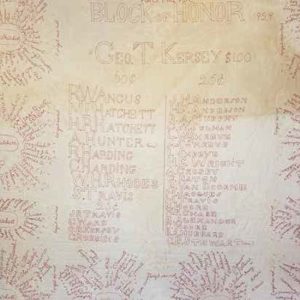

Fundraising quilts were often created to help community members who were ill or in financial distress and to help ensure the community’s survival. On this Forget-me-not signature quilt (1929), the size of each donation is indicated by the size of the signature.

Fundraising quilts were often created to help community members who were ill or in financial distress and to help ensure the community’s survival. On this Forget-me-not signature quilt (1929), the size of each donation is indicated by the size of the signature.

North Buxton has survived into the 21st century, despite all early predictions and indications to the contrary. It has witnessed many magnificent accomplishments through the years, including those of its teachers, postmasters, industry leaders, ministers, farmers and organizations. As we look back down the road where houses once stood, the memories of these people and their times still linger. We can see the footprint they left memorialized in fabric. At the same time, Buxton’s next generation is finding its roots, creating family quilts with pictures, beads and pieces of cloth that continue to tell marvelous stories, honoring their past by reflecting on the simpler life and times of bygone days. They have come to realize the importance of preserving the memory and the heritage that is woven within the fabric of this community. The quilting tradition continues, keeping the legacy alive.

It is very interesting to see how quilting was for so many years a part of this community, then faded, and now shines bright again, still telling stories, keeping people connected once more.

THE QUILTERS

Meet some of the women who worked tirelessly beside their husbands in the fields or settled in larger towns. They left their stitch on the fabric of their community and shared a tradition that remains vibrant today.

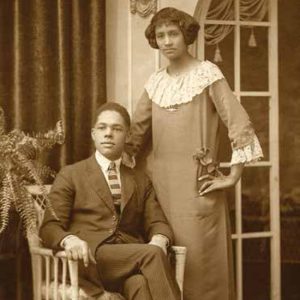

(L) The Watts family came to Buxton from Maryland. Julia was an excellent cook, wrote poetry, played the piano and was always working on a prize quilt or crocheting extremely fine patterns.

(R) Isabel Garel and her husband arrived in the Buxton settlement from Virginia shortly after 1849 and were quite involved in the church.

Verna Shadd always had a meal ready and the table set ahead. Kind and generous, she worked in the grocery store and enjoyed the quilting bees.

Verna Shadd always had a meal ready and the table set ahead. Kind and generous, she worked in the grocery store and enjoyed the quilting bees.

Shannon’s mother, Yvonne Robbins, was a homemaker and farm wife, also working in Chatham’s Public General Hospital lab. A drum majorette in the North Buxton Maple Leaf Band, she loved to sing and belonged to several quartets and choirs. Quilting was also high on her list of favourite pastimes.

Shannon’s mother, Yvonne Robbins, was a homemaker and farm wife, also working in Chatham’s Public General Hospital lab. A drum majorette in the North Buxton Maple Leaf Band, she loved to sing and belonged to several quartets and choirs. Quilting was also high on her list of favourite pastimes.

(L) An excellent piano player, Julia Shreve could often be found at the quilt frame, sharing stories and recipes.

(R) Quiet and soft-spoken, Margaret Newby was Treasurer of the Women’s Council, who made many quilts as fundraisers. Her husband, William, was a farmer and the town cobbler; he enjoyed braiding rugs. A man who always had wonderful stories to share, it is fitting that the Buxton Museum today stands on property once owned by him.

(L) Before school buses became available, Corinne Prince, Shannon’s mother-in-law, drove children living in the rural area to school in her car. Quiet and soft spoken, she too was active in the church and was Treasurer of the Missionary Society.

(R) A founding member of the Busy Bee Club, Constance Robbins was a dedicated member of the B.M.E. Church and the Ladies Sewing Circle. Caring and thoughtful, she was good at sharing words of wisdom. Quilting bees were held in her front room, where the quilt frame would be placed near the wood stove.

Shannon Prince is the Curator of the Buxton National Historic Site & Museum. She is also a storyteller and participant in historical re-enactments which bring the history of Buxton and the Underground Railroad to life for many groups both here and further afield. A descendant of the early fugitive families that came to Canada for freedom and opportunity, she brings insight, respect and a love for this chapter in our history. She still actively farms with her husband Bryan and their four children. When she is not at the museum or on the tractor, she can be found in the kitchen cooking; she also enjoys reading and playing baseball.

To learn more about this important part of Canada’s history, watch the Underground Railroad Explained video.