The fit of your mask does matter.

‘Fit for purpose,’ according to the MacMillan Dictionary, is something that is good enough to do the job it was designed to do.

There were four cloth masks in the package I put in the mail, not just the two requested. They were going to the out-of-province mother of a gal to whom I had given a couple of masks a month earlier. Mom had worn one of her daughter’s masks and appreciated that it was comfortable and stayed away from her lips when she talked, so wondered if I might make a couple for her. My challenge was that the daughter’s masks were size medium, and her mother has a smaller, leaner face. Deprived of the opportunity to physically fit a mask on her, I simply made both medium and “petite”, inviting her to keep the ones that fit best, and donate the others to someone else.

The point is that the fit of your mask does matter. I so often see people wearing masks in public that are way too small, gaping on the sides, sliding off the nose, and most annoyingly, clinging to their lips. (Don’t even get me started on how many have a mask over their mouths, but leave their nose uncovered!) From the beginning of the COVID pandemic I have been actively searching for the best possible mask materials and design. I have sewn 10 or 12 different mask patterns looking for the best fit, experimented with different nose pieces and head attachments, and followed the research to understand the best materials. Each time I discovered a better version, I made additional masks for family and friends as I want them to have the highest possible level of protection.

A recent CBC article headline reads: “Why you might want to start wearing better masks – even outdoors“, and leads with: “The spread of more contagious coronavirus variants in Canada amid already high levels of COVID-19 makes it a critical time to think about the masks we wear”.

The article appears to favour surgical masks over cloth masks. Why? Well, I know that surgical masks are standardized and as such are supposed to deliver a certain predictable standard of protection. But there are off-brands available that may not, in fact, meet the standard. Surgical-type masks are usually one-size-fits-all, they tend to gape at the sides, and, despite the fact that they are disposable, intended for one-use-only, many people wear them again and again for convenience or to save money. Did you know that the melt-blown polypropylene middle layer of surgical and N95 masks is manufactured with electrostatic properties that can help trap virus particles? This is great technology, but the electrical charge dissipates over time “exacerbated by the warm humid environment created by respiration during use” (PDF), so recommended maximum wear-time is often only 4-8 hours.

Cloth masks, on the other hand, can be configured in various sizes to fit the face and are washable and reusable. Current WHO and Health Canada recommendations are for a middle layer of spunbond polypropylene that can be safely washed and reused and which does not depend on electrostatic properties to be effective. Learn more about polypropylene and where to get it here. I understand the reluctance of leaders to recommend cloth masks, given that there are hundreds of different patterns and materials, and no standardization. My personal belief is that a well-fitting cloth mask constructed with quality materials including the recommended filter layer and appropriately cleaned can provide safe and sustainable protection.

My personal belief is that a well-fitting cloth mask constructed with quality materials including the recommended filter layer and appropriately cleaned can provide safe and sustainable protection.

Health Canada agrees, stating in a recent release:

A well-fitting mask should:

- be large enough to completely and comfortably cover the nose, mouth and chin without gaps and not allow air to escape from edges

- fit securely to the head with ties, bands or ear loops

- be comfortable and not require frequent adjustments

- maintain its shape after washing and drying (for non-medical masks only)

A well-constructed and appropriately sized cloth mask fits better than a surgical style mask.

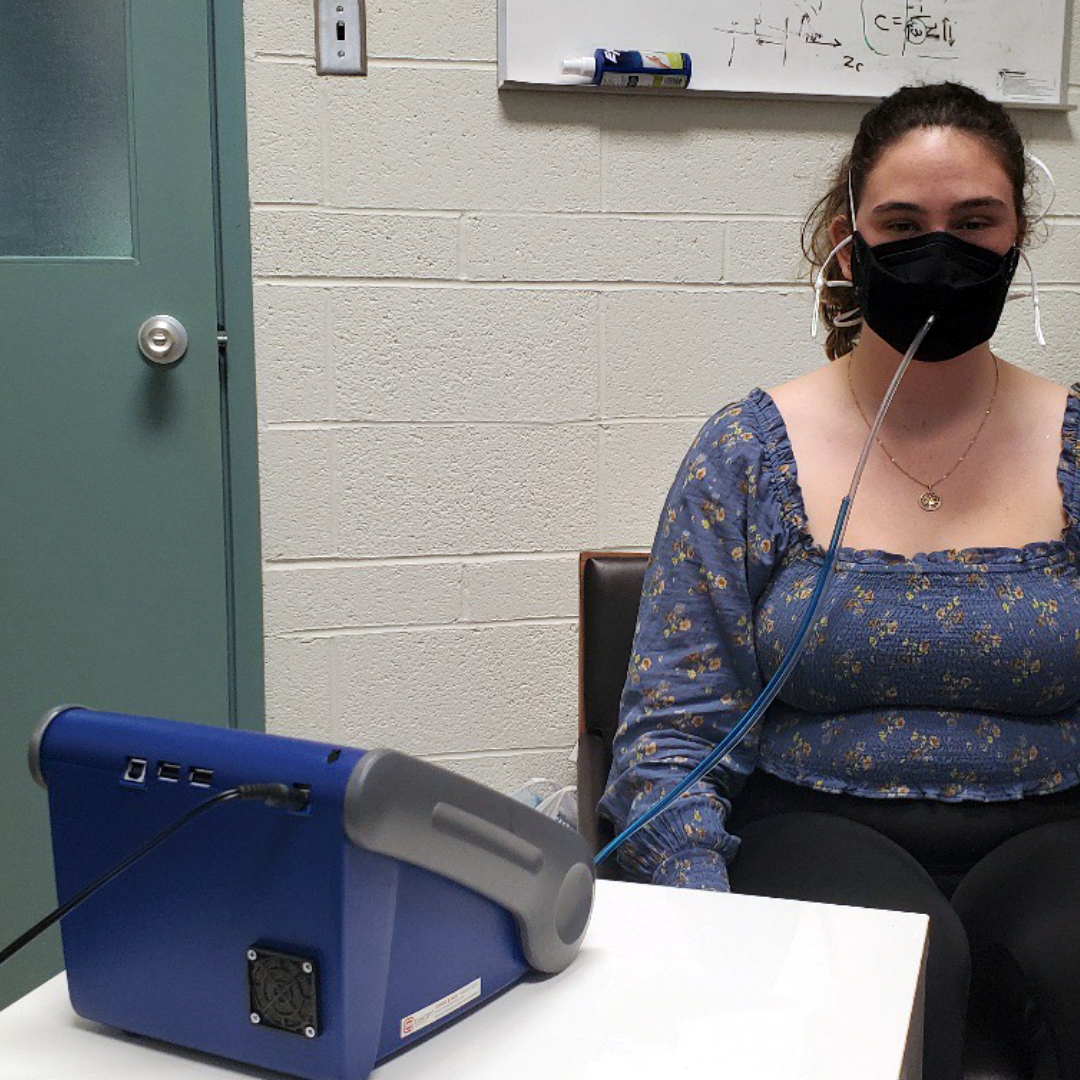

Scientists are currently working to provide more definitive data on the filtration efficiency of cloth masks when they are made with appropriate fabrics and the recommended polypropylene filter layer. I recently had the opportunity to speak with three bright young women who are conducting mask materials and fit testing in a lab at McMaster University’s (Hamilton, ON) Centre of Excellence for Protective Equipment and Materials (CEPEM).

Amanda Tomkins, a fourth-year student in Electrical and Biomedical Engineering, Gurleen Dulai, a fourth-year Chemical and Biomedical Engineering major, and Ranmeet Dulai, who is in her fourth year of a Health Sciences degree described the process in the lab in lay terms for me.

Using volunteers who have all met the measurement criteria for ‘medium’ size according to the internationally recognized NIOSH panel, two different types of testing are being performed on cloth masks:

- Materials testing will reveal differences between masks made with the exact same pattern and specifications, constructed in 4 different fabrics, each made with – and also without – the polypropylene inner layer.

- Fit testing will reveal differences between seven different mask designs, all size medium, made with exactly the same materials, most incorporating a sewn-in spunbond polypropylene layer. Testing encompasses both quantitative and qualitative criteria.

Qualitative (scientifically measured) data is obtained using a Portacount machine. Tiny particles of NaCl (salt) the same size as airborne particles containing the COVID virus are released into the environment near the test subject. The concentration of particles outside the mask and inside the mask are compared to determine the ‘filtration efficiency’ of the mask. This will show the percentage of particles blocked by the mask.

Qualitative data is also gathered: the test subjects are asked to rate the relative comfort of the mask and other attributes such as air leakage detected around the mask and fogging of glasses.

Study participants volunteer for at least 1½ hours in order to complete all of the tests. They are asked to perform a number of specific actions in sequence including breathing normally, deep breathing, turning their head, nodding, reading a few paragraphs from a script, standing up and bending over. Each function is timed and additional measurements are taken.

The results of this testing will take time. Calculations and analysis will be followed by careful documentation and peer review before they are published.

Amanda Thompkins, who is both a tester and participant in the study, is wearing a test mask connected to the Portacount machine.

I was privileged to be able to submit a mask design for testing. The design I chose to make is the modified 3-D mask, which has great fit around chin and sides, utilizes the sewn-in spunbond polypropylene filter layer with good quality quilting cotton, commercially available flat aluminum nose strips, and adjustable ear loops. This is quick and easy to make, comfortable to wear, and stands out from your mouth. The instructions are available in the files of the Quilting in Canada Facebook group page. I am excited to see how it compares to the other mask designs when the results of the testing are published.

Meantime, I am feeling confident about continuing to make and give Fit for Purpose cloth masks to protect my family friends and community.

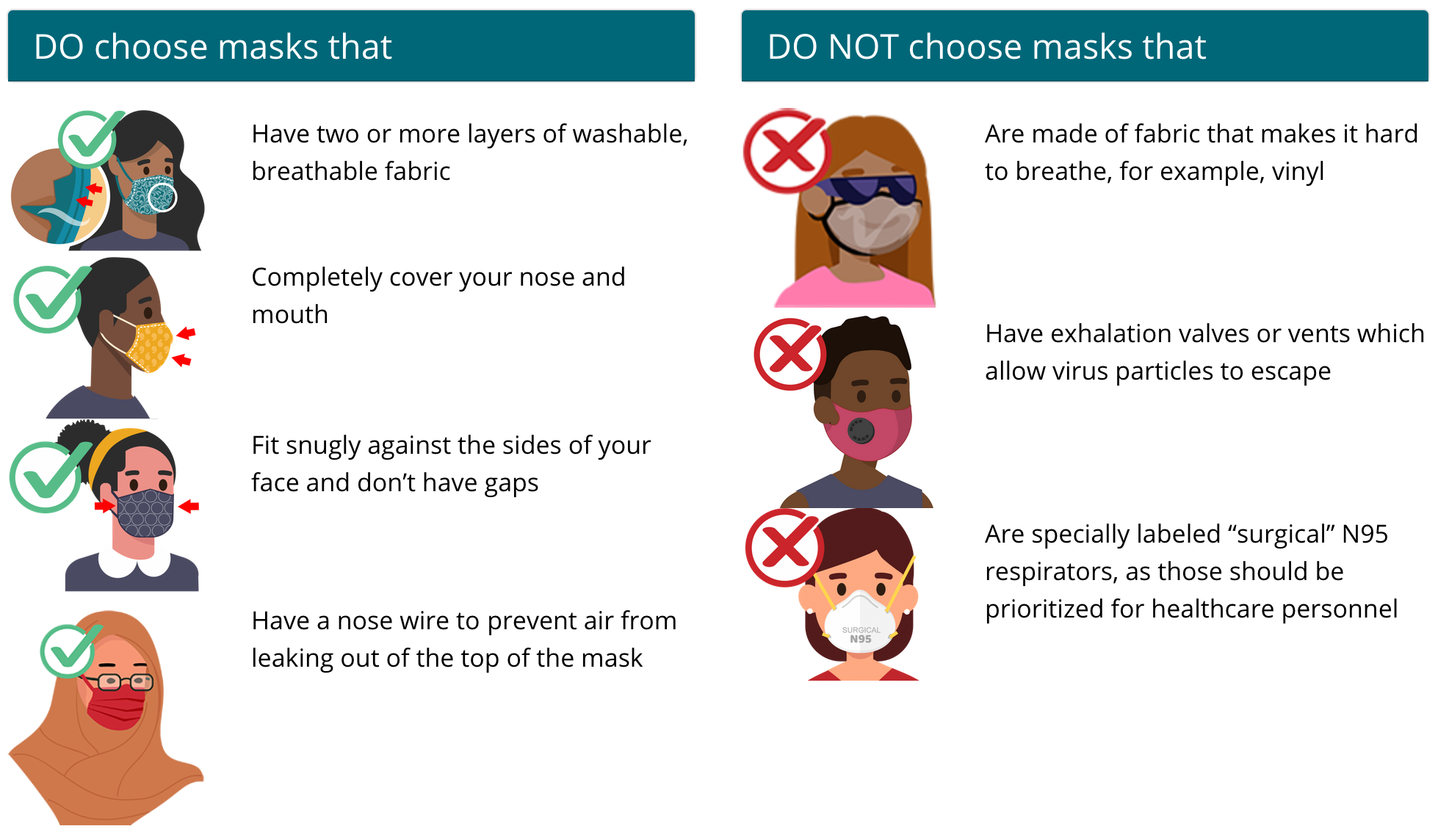

Do’s and don’ts from the CDC’s Guide to Masks.

About the Author: Barb Round has been quilting and creating for 50 years (!!). She is a former CQA regional representative for NWT and BC, and currently serves as the CQA Liaison to the Cloth Mask Knowledge Exchange group, which has input to and disseminates information from the Centre of Excellence for Protective Equipment and materials at McMaster University.